Blog

Liliana Porter: Starting Out

In this excerpt from Liliana Porter in Conversation with Inés Katzenstein, Porter reflects on her early years as an artist and how her family’s influence shaped her perspective and work.

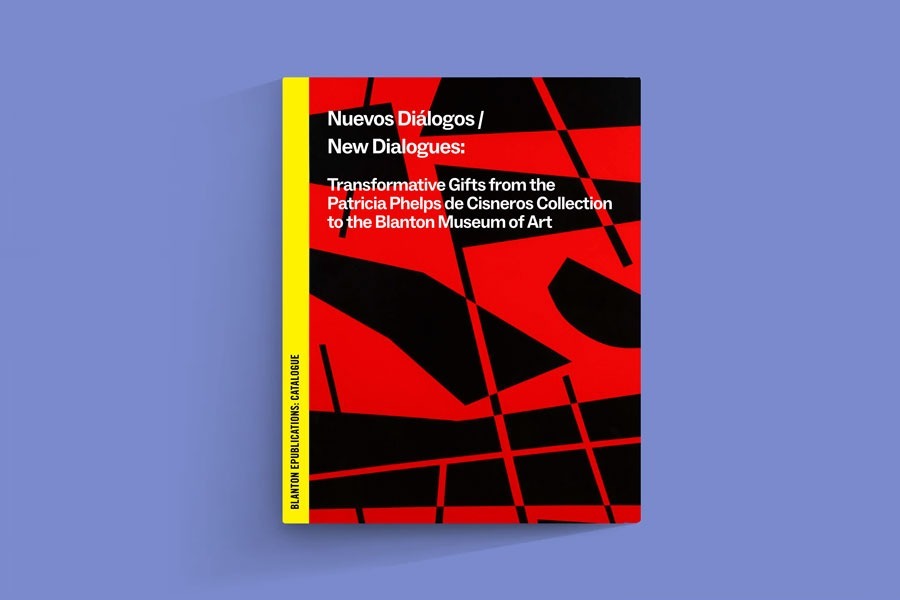

Published by Fundación Cisneros/Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros in 2013, the book is available to read and download for free.

Inés Katzenstein (IK): What is your first memory as an artist?

Liliana Porter (LP): I think it might be from 1958, when I was still a student at the Universidad Iberoamericana de México, and some articles about my work were published in the newspaper.

As you can see, I remember when others used the word “artist” to speak about me. But as for me defining myself as an artist—that’s something I definitely don’t remember. It’s hard to say whether “artist” is a positive or negative word, wouldn’t you say?

IK: What makes you say that?

LP: Because the word “artist” has something of “actor” in it. In other words, something kind of fraudulent, and it’s also the kind of word used by someone who wants to define oneself as different, which is not very appealing. Whenever someone categorically announces “I am an artist,” I immediately begin to suspect that he or she must be kind of stupid, or at the very least there is a high probability that his or her work is a bit mediocre. It’s like answering the question “What do you do?” by saying “I am wise.”

IK: There is something that struck me more and more as I got to know you, and that is the fact that your perspective on the world, in an everyday sense, is as intense, lucid, and humorous as the world vision that your artwork manifests. The surprise, innocence, or cruelty exuded by those little dolls in your photographs is the same surprise, innocence, or cruelty with which you gaze at what’s going on in your garden through a window in your house. Is your work the consequence of a gaze that reveals a previously felt sense of alienation with the environment around you, or was that gaze something you slowly built and cultivated, until it became who you are?

LP: I may be too close to myself to be able to realize or analyze what you are asking. In reality I think everyone is like that, because how can you dissociate what you are from what you do? It would be so much work!

IK: What I am trying to say is that your work, to a greater degree than the art of other more formalist or content-driven artists, seems to be the direct consequence of a clear transposition of a particular way of looking at reality. At the same time, of course, we can also ask ourselves to what degree that way of looking at the world is informed by the work.

LP: You must be right. I was also probably influenced by the atmosphere in which I was raised, by an intelligent father with a tremendous sense of humor and a mother who reinvented her reality because of some terribly difficult childhood experiences. I believe it was very influential to witness how my mother, instead of becoming a bitter, angry, or negative person, built a life with a great deal of compassion, in a perpetual state of awe for, or awareness of (though it may sound corny), the mystery of the perfection that one finds in nature. I was also very influenced by the way she developed a kind of basic faith in human beings, or in life, or maybe it was simply just a basic, abstract faith.

I think all those things helped me to perceive the world and the things in it. Then, as I grew up and began to develop my artistic practice, themes began to emerge on their own that I found interesting both in my life and in my work at the same time.

IK: Reading some letters you wrote to your family when you were very young and living in New York, in 1964, it is clear that you already possessed a very sophisticated sense of humor that must have come from your father, a famous writer and humorist. Can you tell us who Julio Porter was, and what he did?

LP: According to Wikipedia (and this is true), “Julio Porter ( July 14, 1916, Buenos Aires–October 24, 1979, Mexico City) was an Argentine screenwriter and film director and known as one of the most prolific in the history of the cinema of Argentina. He wrote scripts for over 100 films between 1942 and his death in 1979. He directed 25 films between 1951 and 1979.”

He was that and much more…I got along very well with my father. He was a lot of fun, and very smart, and he supported me unconditionally. He was not, exactly, an archetypical father, in the sense of someone who would go around giving you transcendental advice or anything like that. That role was fulfilled by my brother or my mother. My father was a well-known figure in Argentine film, radio, and theater. I was very proud of my family, of my house, and of him, and I felt very lucky to be his daughter. My father loved his friends, their parties, restaurants, and people in general. He was a lot of fun, but he could also be very irresponsible and uncontrollable. Being with him was not always fun or easy for my mother, most likely because she was desperately in love with him, even after they separated. They would write poems and letters to each other, they were always creating dramas, fighting and then getting back together…they were straight out of an Italian movie!